Gintarė Sokelytė, * (Asterisk)

* (Asterisk), 2023–24

Room installation

Plaster, branches, wood and jute fabric

40 m2, Height 2,5 m

Video installation

Five videos 7:04 min, 3:44 min, 6:15 min, 4:21 min, 11:00 min

Wood, MDF, cardboard, paper and 5 screens

3 x 3 x 3 m

Sculpture

Metal

92 x 68 x 210 cm

Courtesy the artist

The body is a material unit with which the individual inhabits time in the here and now. But what constitutes our existence? What is the irreducible essence of human existence? What is humanity when it’s no longer governed by its self-created structures of order?

For her new exhibition, Gintarė Sokelytė has constructed a self-contained universe. She transports the viewer away from their familiar sense of perception and releases them into a constructed parallel world. Like through a rabbit hole, the space can only be entered via the elevator. The door opens, and we find ourselves in a prehistoric cave. Sokelytė has painstakingly recreated part of the Blombos Cave in South Africa, using scientific 3D models. Blombos is the oldest Stone Age site where evidence of human creativity and culture has been discovered. Stone engravings depicting intersecting lines, painted with ochre, and numerous artefacts testify to the fact that 71,000 years ago Homo sapiens thought in abstract terms. They had to possess the ability to imagine, synthesise and visualise things. And the result was their rock art—the few traces left of human beings from ancient times, and evidence of their need to create images and symbols that bear witness to rich inner worlds.

These first traces of human art, the first visual language of early humans, are what Gintarė Sokelytė picks up on. Through her multimedia installation entitled * (Asterisk), which faces the cave, the primal symbol of prehistoric rock art inspired her to create her metal sculpture. Sokelytė welded it to the size of a human body—this recurring symbol of humanity, found from the Blombos Cave to the digital world. She then tied five people, five volunteers, to the metal star by their arms and legs. Bound to this cruciform sculpture, she then interrogated them about fear, power and order. How do you describe fear? What are you most afraid of? What if this happens? What is power? Who is allowed to wield power? Describe your understanding of order. How do you feel when reality slips away from you? What forces make you feel powerless?

These five people were interrogated through constant, cyclical repetition, each speaking in their respective native language and allowing their bodies to be subjected to external coercion. Exposed to the lens of the camera, their bodies began to ache from the gravitational force exerted on them. They surrendered to the influence of this external force until, in a transcendent state of essentiality, they gained deeper insight into their own perception of society and the self.

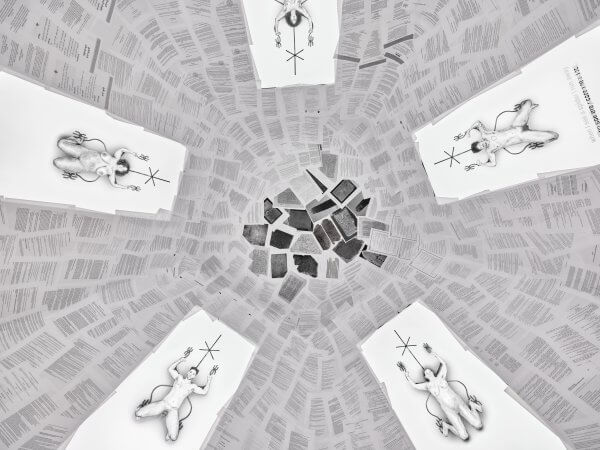

The result is five films forming part of a large geometric sculpture—a dodecahedron, a geometric construction with twelve equal faces and thirty equal edges. The viewer may enter the structure, brightly lit from the five monitors, and listen to the five volunteers as they question their innermost selves on notions of fear, power and order. In geometry, the dodecahedron is one of the five Platonic solids. Plato assigned them to his worldview as fundamental geometric figures, and their significance remains fundamental to mathematics and science today. Due to its perfect symmetry, the dodecahedron is considered the most sacred of the five Platonic solids, and the golden ratio is found repeatedly within it. In Plato’s time, it was even forbidden for people to speak about the figure. It symbolised the soul of the world (the ether) and the universe, and its twelve faces draw a connection to a number that holds special significance for human systems: the twelve zodiac signs, the number of months or hours within units of time, all the way up to the twelve apostles. For Gintarė Sokelytė, the dodecahedron forms a conceptual counterpoint to the primordial nature of the cave.

Its interior is lined with numerous copies of texts, which Sokelytė has researched and printed, from ancient to modern codices. Nearly two hundred international state constitutions and around forty collection of laws, from prehistory to the present, have been arranged chronologically and mostly in their original national languages. For the artist, they represent humanity’s struggle for structure. Laws are both protection and restriction, defining a transition in human history towards a normative order for communal life. Sokelytė explores a timeless urge with which one resists the uncertain through order and form.